By Barbara Paterson

|

|

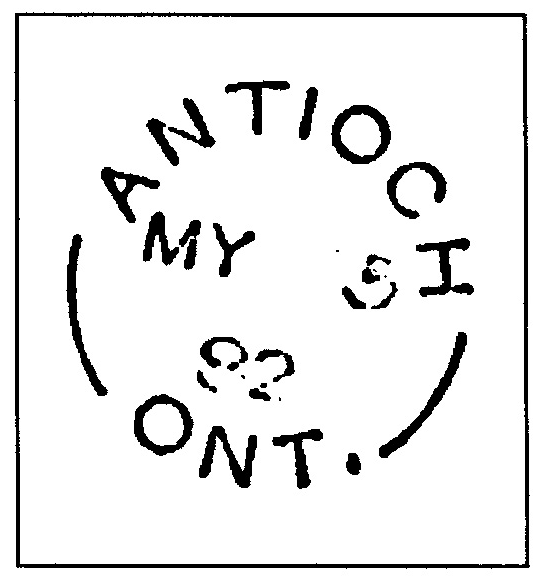

Antioch proof strike of May 5, 1882

|

From “Stories of the Past,” Muskoka Sun, July 20, 2006; The Sinclair Raconteur’s Anthology: Barbara Paterson’s Published Stories, eds. W. Dan Mansell, Carolyn Paterson, and Marlene Walker (Peterborough: asiOtus Natural Heritage Consultants, 2014).

Republished with permission of Metroland North Media and asiOtus natural heritage consultants.

A ghost town is defined as being a deserted or abandoned town. For me, the term triggers an image of abandoned mines, bar room brawls and shootouts in corrals from American old west history.

In Muskoka, with few exceptions, all the so-called ghost towns were originally post offices. Our “ghost towns” are in fact “ghost offices.”

Before the telephone became a fixture in our homes, the post office was the only means of communication with family who lived, sometimes, not that far away. Newspapers and periodicals came by mail, business transactions were conducted by mail and products offered for sale in catalogues were “mail-ordered.”

Post offices were located in the postmaster’s home and when a postmaster resigned, for whatever reason, the post office moved to the home of the next postmaster. It mattered not where you (the patron) lived because your address was the post office wherever it was located. It was up to you to know who the postmaster was, where he lived, and therefore, where you could pick up your mail.

|

||

|

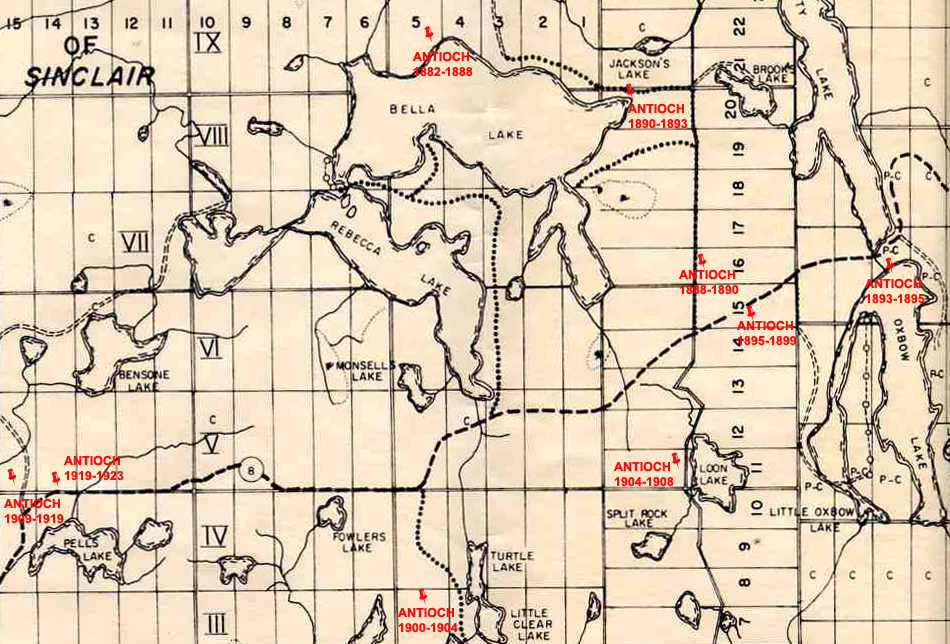

Your address was Antioch, wherever it happened to be. |

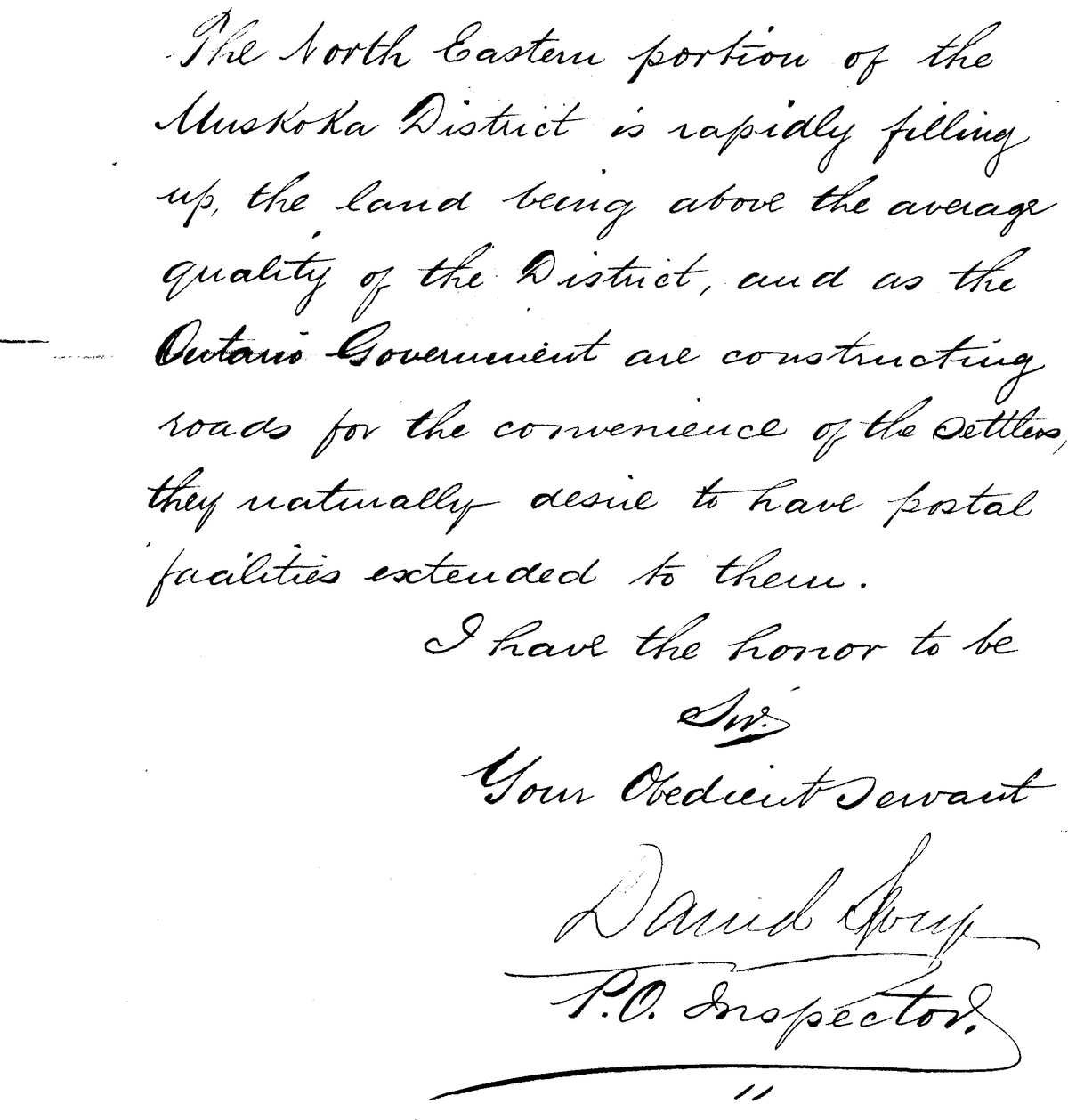

All post office business passed across the desk of The Honourable Postmaster General at his office in Ottawa. He had a staff of post office inspectors who lived in convenient urban centres across the country, and who, on the Postmaster General’s instructions, dealt with problems and complaints and established new post offices.

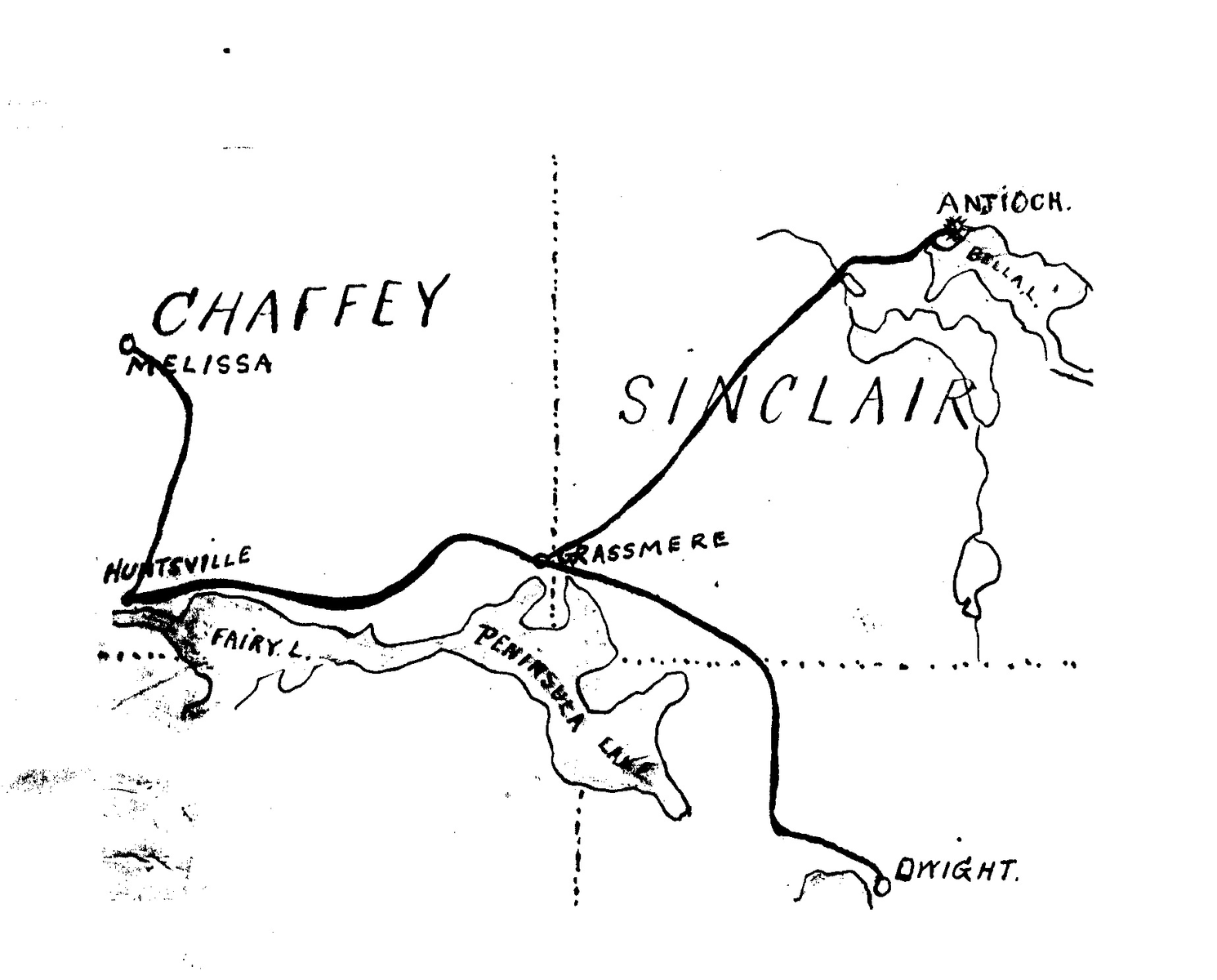

Soon after Sinclair Township was surveyed in 1876, a large group of inter-related families located free land grants in the township. Before the Antioch post office was established, these people’s address was Grassmere, and that’s where they walked to get their mail.

The Antioch Post Office opened March 1, 1882, in the home of Edmund Garnet. The post office inspector, Daniel Spry (who lived in Barrie), had written in glowing terms to the Postmaster General of the potential for this post office: “Antioch, the site named for this proposed office is situated about 10 miles north of Dwight and about 12 miles northeast of Huntsville in a well-settled neighbourhood that is improving, the lots being rapidly taken up and settled upon. The land is reported to be of very good quality. There is no village or stores or taverns and other places of business near the proposed site on the Government Colonization Road. About 30 families would be served by an office at Antioch, the revenue of which would be about $40 per annum. The site is a very convenient one for the settlers residing in Sinclair, which Township is entirely without a post office. Should you be pleased to grant the prayer of the petitioners, one mail per week can be supplied from Grassmere at about $60 per annum.”

After only five years, Edmund decided to move away from the area and his nephew, Joseph Russell, moved to his house and looked after the post office. Joseph himself resigned a year later. The Antioch post office was about to be dissolved unless another postmaster could be found!

In short order, the settlers prepared two petitions that Muskoka M.P. Colonel O’Brien received a month later on April 17, 1888. Both petitions requested that Antioch post office be removed to a more convenient site. The first pleaded to have the location changed to Mr. John Lee’s in Concession B, Lot 16, 17 on the Bobcaygeon Road. This was the most central place they said.

The second petition asked that the location be moved to Lot 3, Con[cession] 7 in Finlayson Township, to William Hood’s General Store, a more suitable place for a post office. Two weeks later, at a prearranged meeting called for noon (presumably at the first Antioch location), Mr. Spry met with 34 people. He reported that quite a lively interest was taken in the matter under consideration as both Mr. Lee and Mr. Hood spoke in defence of their individual locations.

In his report to the Postmaster General, Mr. Spry noted that Mr. Lee’s was the most central location and on a public road. Not only was Mr. Hood’s store out of the way on a private road[;] he felt Mr. Hood would be particularly obnoxious in the position of postmaster, owing to improper remarks made by him regarding some of the members of the families of settlers. On the other hand, he said, Mr. Lee is personally unobjectionable and his appointment will meet with approval.

So on September 1, 1888, John Lee became postmaster, a position he held for two years until he returned to his former home in Durham County in August 1890. Andrew Hart’s homestead was approved for the next post office location but the Harts decided to move to a recently abandoned farm on the south shore of Rebecca Lake. They had two daughters and they wanted to be closer to the school.

Then on December 1, 1890, rather than reapplying for a new location, Edgar Joseph Brooks just moved his family from his home on Brooks Lake to the recently abandoned Hart homestead to become the next postmaster. Three years later yet another opportunity presented itself to Brooks when William Hood moved away in the fall of 1893. Brooks promptly resigned as postmaster and George Hart, who had the mail contract to deliver the mail from Grassmere, looked after the post office at his house while Brooks got himself re-established in William Hood’s abandoned store. Then Brooks re-applied as the postmaster and the post office relocated on Lot 3, Con[cession] 7 in Finlayson Township on April 1, 1894.

By the end of that month there was a letter from Richard McBrien, complaining about the move. Again the site was considered out of the way and it was noted it would add two miles more travel for the mail carrier. The Honourable Postmaster General ordered Spry to return to Sinclair Township to review the situation, which he did late in June. He reported that the location in Finlayson served a number of lumbermen as well as settlers. Richard and David McBrien could see the post office from their home at the north end of Dotty Lake and if anything, the new location was more convenient for them, he said. The Finlayson location was approved.

Postmaster Brooks resigned a year later and the post office moved back to George Hart’s home until July 1899 when George announced plans to head for Manitoba. By the end of the month it was relocated again to the new postmaster, Matthew McMaster’s home in the 3rd Concession.

In 1904, Matthew McMaster’s son-in-law, Sam Bloss, purchased the Bravender farm on the Bobcaygeon Road. McMaster resigned at the end of that September and Sam Bloss became the postmaster for the next four years.

A member of the Brantford Hunting Club, Rev. Henry Harper, bought Sam’s farm in 1908. The post office moved again, this time to Henry Field’s home where Henry’s unmarried son George became the postmaster.

In April 1915, George and his brother William were killed at the family sawmill on Pells Lake and their father, Henry Field, took over the post office until he resigned in 1919. The final move was to Robert Field’s home, the former Patty Myles house, where it remained until the office was closed in 1923.

Antioch post office moved so frequently it never had time to become a town. In 41 years it moved at least seven times and when it closed it became just another defunct post office or a “ghost office.” This made-in-Muskoka term is an honest and a more captivating label.