Before 1876

|

|

Bella and Rebecca Lakes from the air, 1970s or early 1980s (Billie Bear Photo Archive, Jill Brown)

|

The traditional names of the lakes were “Little Sand” and “Big Sand.” Who originally named them, and how long ago, we may never know; however, it is interesting to examine some clues.

Before John McAree’s 1876 survey of Sinclair, some settlers had already taken up land in parts of the township. Called squatters, they lived on Crown lands negotiated through the Robinson-Huron Treaties and clustered around the settlements such as Grassmere and Hillside. Although no one is known to have lived on the shores of what would come to be known as Bella and Rebecca lakes until after McAree’s survey, we do know that Indigenous peoples had been using the area for a very long time, eventually sharing their knowledge with the early squatters. Considering the sandy substrate of the area, bulldozed and organized by the last continental glacier, it is easy to assume why the lakes might have been referred to as Little Sand and Big Sand.

One squatter, William (Bill) Green, arrived to the region sometime probably in the 1860s with his father. In 1878, Bill took up lots on Peninsula Lake; however, he had been trapping and fishing all through the area since he was a boy. His father, Sam, lived on Lake of Bays on a peninsula next to the Bigwin family’s seasonal settlement and family burial ground. An account of one of Bill’s fishing trips in October 1876 is relayed by Thomas Osborne, 16 years old at the time, in his story The Night the Mice Danced the Quadrille: Five Years in the Backwoods. Bill took Thomas along on a fishing expedition that would supply winter food for his family, and also for selling and trading in Huntsville for other amenities. The trip was to a remote camp on what Bill called “the Little Sand and the Big Sand.” Bill’s hut, made of split logs, “built upright and close together,” was reached by paddling and portaging through a series of lakes, eventually arriving at Little Sand, paddling through some narrows, and then across Big Sand. The story describes a place where they would “run the canoes into the mouth of the creek near the camp.” Although we cannot know for certain which creek Bill’s camp was near, the description would indicate that it was likely on the north side of Bella Lake, and where the “salmon trout… were running up on the shallows along the stony shores.”

|

||

|

One of four dugout canoes found in Rebecca Lake (Wendy Kimmel) |

|

Known for their intimate knowledge of the region, Indigenous people were often hired as guides. It is reasonable to assume that Bill and his father had gained some trapping, fishing, and other local knowledge from the Ojibwa families that were still using the area in those very early settlement years. It is also documented that members of an Ojibwa Crow family were hunting in the Big and Little Sand Lakes area up until at least 1877. That year, two hunters came through Henry Field’s new claim on the western shores of Pell Lake. The hunters were carrying deer, and they invited Henry to eat at their campsite, also on Pell Lake. Henry stayed with them for three weeks and they helped him build his shanty.

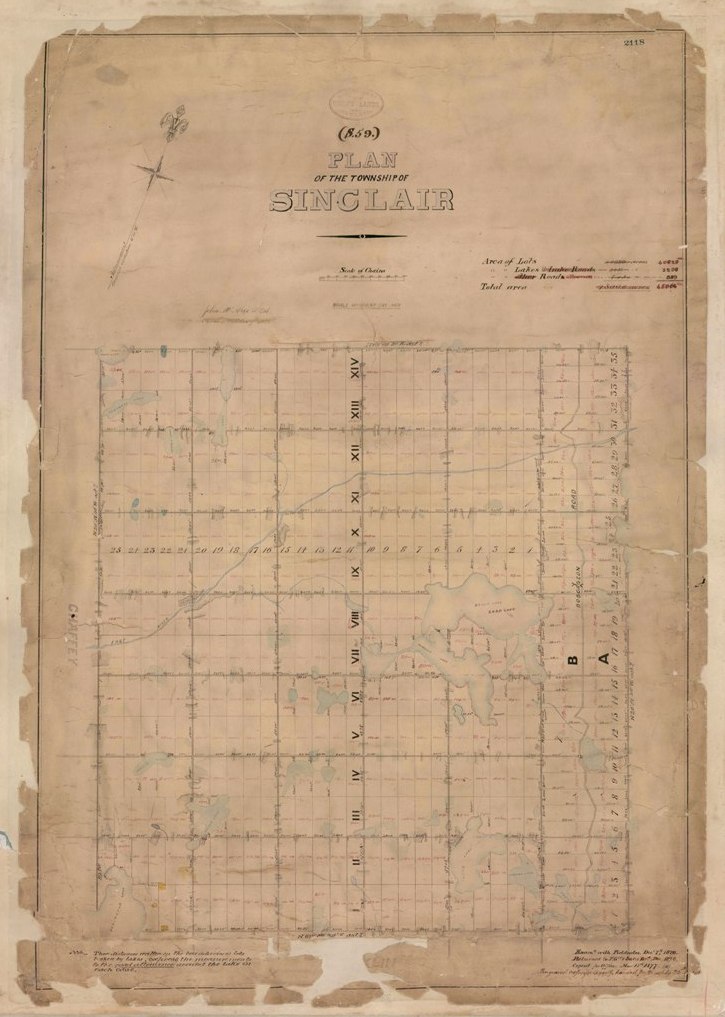

Rebecca and Isabella

Between May 16 and October 9, 1876, McAree conducted his survey, including all around “The Little and Big Sand” lakes. In fact, Thomas Osborne relates that, during his trip with Bill that October, he ran into the blaze “marks made … by surveyors whom I knew had been through, surveying and laying it out into one-hundred-acre lots for homesteaders.” When McAree came through on his survey earlier that summer, he may or may not have known what Bill Green, or the Ojibwa hunters, called the biggest lakes in this part of their hunting, trapping, and fishing grounds.

|

||

|

John McAree’s survey of Sinclair Township, 1876 (2118-C24-SINCLAIR) |

|

Traditional place names that had been determined by the Indigenous users of the land were often changed. Early nomenclature for locations, during surveys such as these, would often be determined by honouring squatters who had already arrived on the land. Such was the case for Walker’s Lake, where Robert Walker had already built a sawmill by the time the survey came through. As no one had been squatting or had yet settled on the Little Sand and the Big Sand, there was an opportunity for McAree to assign names of his own choosing.

McAree was born in 1840 near New York City. He came to Canada and had a career that had him travel often, and for long periods of time, as a land surveyor working all across the country. At some point, while in Toronto, he met his future bride, Rebecca Fleming. Rebecca and her twin sister Isabella were born in Ireland in 1844 and survived a rough Atlantic crossing to Canada at the age of three, during which three of their siblings died. The sisters were raised in Cabbagetown in Toronto. In 1871, Isabella married Joseph Thompson but, in 1873, died giving birth to their first child. Later that year, Rebecca and McAree were married, and in 1876, the year John was surveying Sinclair, she had their first child. Rebecca had two more children, but in 1882, two weeks after the birth of their third child, she died from fever. The child, a daughter also named Rebecca, died four years later from diphtheria.

We cannot know for sure, but it would seem safe to assume that our “twin lakes” were named by McAree in 1876 to honour his late sister-in-law, Isabella, and her twin, his wife Rebecca.

|

|

|

| Rebecca Lake from Sunset Cabin, 2004 (Wendy Kimmel) |

Bella Lake from the Foundation beach, 1998 (Val Kremer) |

Sources:

Mansell, W. Dan, and Carolyn Paterson, eds., Pioneer Glimpses from Sinclair Township, Muskoka (Peterborough: asiOtus Natural Heritage Consultants, Barbara Paterson Papers, 2015).

McAree, Vern, “Cabbagetown Store” (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1953); accessed online through the Cabbagetown Regent Park Museum).

Osborne, Thomas, The Night the Mice Danced the Quadrille (1934), reprinted as Reluctant Pioneer (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2012).